3:20PM MT update: The outage is has ended.

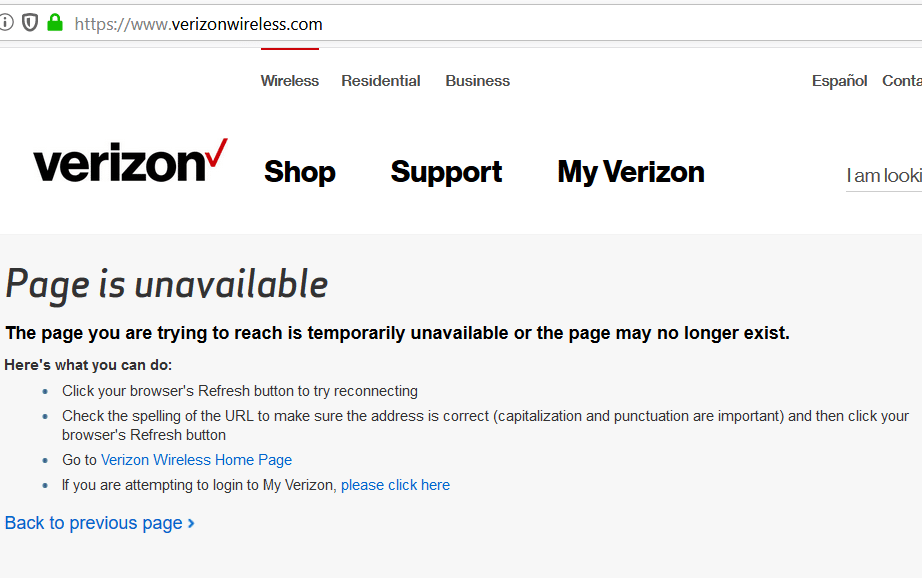

VerizonWireless.com appears to be down at the moment. If you’re having trouble accessing the website right now, the issue is not on your end. As far as I can tell, the problem is not related to the browser or device visitors are using to access Verizon’s website.

At the moment, I’m being served a “Page is unavailable” message on all of the web pages I’ve tried to load:

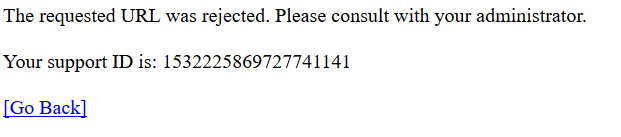

Earlier, I was presented with a different error message:

The outage appears to be unrelated to the locations users try to access Verizon’s website from. I continued to receive error messages when accessing Verizon’s website from other locations via a VPN.

The outage appears to have started by about 1:30MT and hasn’t been resolved at the time of writing (about an hour later). Android Central and at least one Twitter user have also picked up on the outage.

Stay tuned.