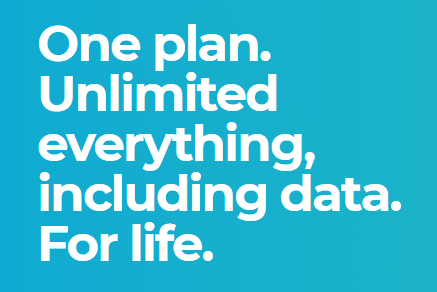

Altice Mobile just launched with a tempting offer. Altice’s only plan, its “unlimited everything” plan, is only $30 per line each month.1 A lot of technology websites have been writing about the new offering, and most of them aren’t mentioning how many limits Altice places on its subscribers.

(Added 2/26/2020: Since this post came out, Altice Mobile’s price has changed to $40 per month for most people and $30 per month for Optimum and Suddenlink customers.)

Limits

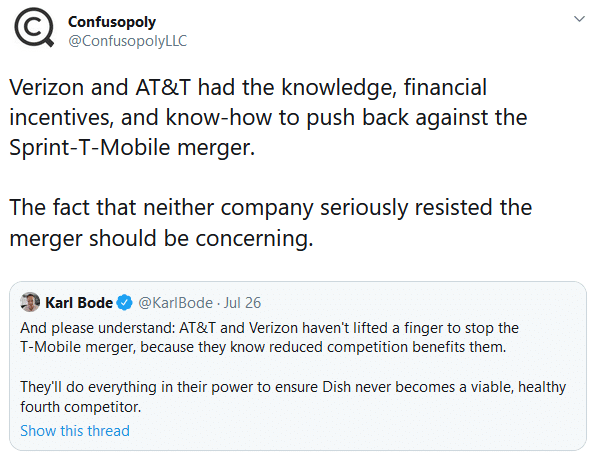

In my previous post, I was critical of Total Wireless for marketing one of its plans as an “unlimited” plan, even though it involved a significant limitation:

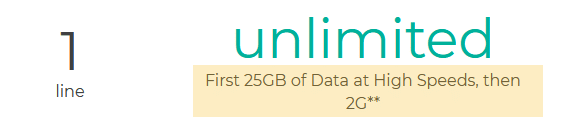

Total Wireless is at least is transparent in letting customers know that limits exist despite the plan’s unlimited label. Altice Mobile doesn’t put a disclaimer or an asterisk next to its claims:

Altice’s press release is even more misleading:2

- unlimited data, text, and talk nationwide,

- unlimited mobile hotspot,

- unlimited video streaming,

- unlimited international text and talk from the U.S. to more than 35 countries, including Canada, Mexico, Dominican Republic, Israel, most of Europe, and more, and

- unlimited data, text and talk while traveling abroad in those same countries.

Potential customers wanting to understand Altice Mobile’s limitations need to find their way to a web page full of legalese titled Broadband Disclosure Information.3 As it turns out, Altice has lots of limitations:

- Mobile hotspot is typically throttled to a maximum of 600Kbps (a fairly slow speed).4

- Video is typically throttled to a maximum of 480p.5

- After 50GB of use in a month, video traffic and hotspot traffic are throttled to 128Kbps.6

- Roaming data is throttled to 128Kbps.7

As I discussed in my last post, it’s silly to call a service unlimited while throttling to sluggish speeds. The claim in the press release that Altice offers “unlimited video streaming” is particularly misleading. 128Kbps can’t even support stable streaming of low-resolution video.8 Turns out the claim of unlimited international data in 35 countries is also misleading. International data after the first gigabyte is throttled to 128Kbps.9

Despite the limitations, there’s a lot that’s exciting about Altice Mobile. The service has a competitive price. It might be a good option for people who live in the regions where it’s available.

I hope we’ll see Altice move towards being more transparent with consumers.