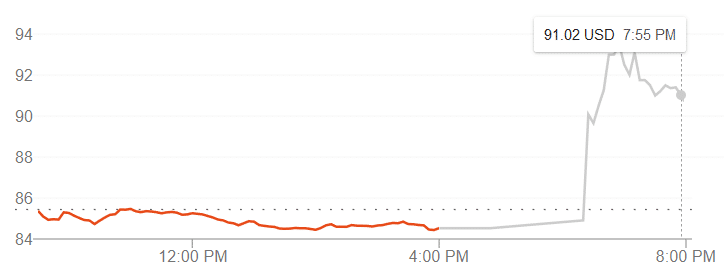

A major T-Mobile network outage is going on right now.

T-Mobile’s outage

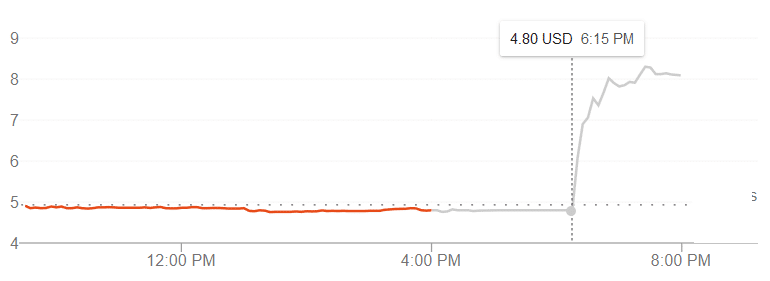

T-Mobile subscribers scattered around the U.S. have been reporting that calls and texts have been failing over the last few hours.

The outage appears to be affecting more than T-Mobile’s direct customers. Subscribers with mobile virtual network operators that run over T-Mobile’s network are also reporting problems.

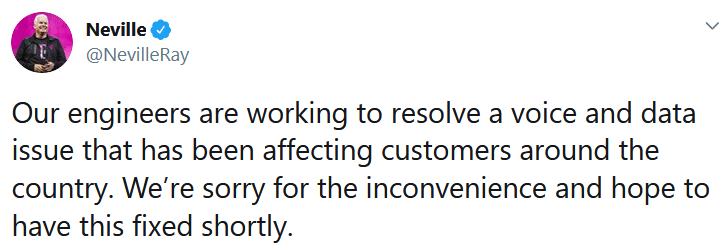

T-Mobile is aware of the issues. Neville Ray, T-Mobile’s President of Technology, shared the following tweet:

While Ray describes it as a “voice and data issue,” most of the reports I’ve seen so far have been about issues with calls and texts.

Other companies

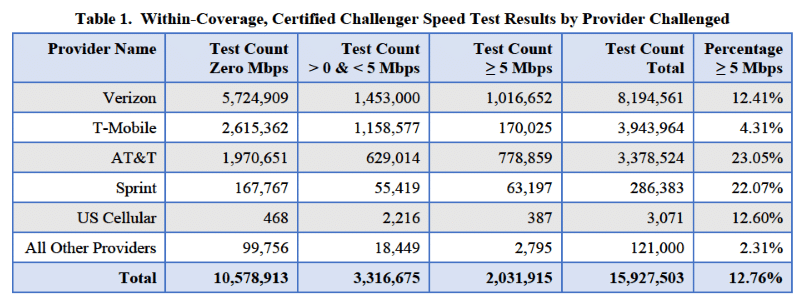

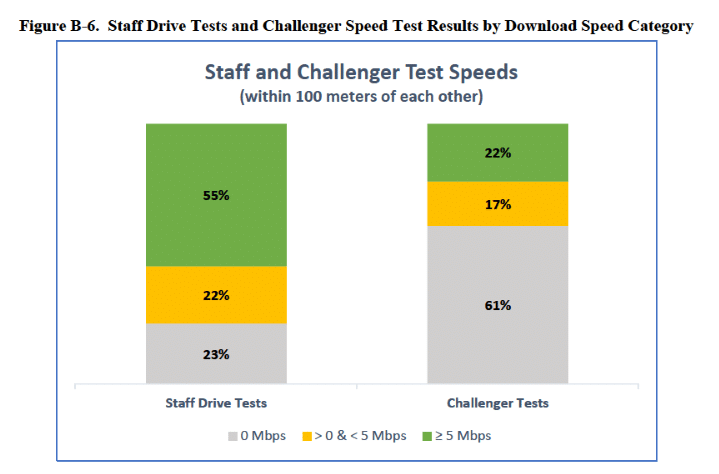

The website Downdetector is recording an atypical number of issues with a bunch of wireless carriers, Facebook, Instagram, Twitch, and a handful of other internet companies. It’s unclear if Verizon and AT&T are experiencing any issues of their own. Subscribers with these carriers may only be experiencing issues when they try to contact people on T-Mobile’s network.

Prognosis

At this time, I have not seen any word on what is causing the outage. I have also not seen any clear indication about when the issue is expected to be resolved.

I plan to make updates as I learn more. This may end up being one of the largest network outages in the U.S. in years.

Monday Night Update:

At 11:03pm MT, Neville Ray tweeted that the issues have been resolved: