AT&T has been running an ad campaign with commercials where the company claims to offer the best network.

These commercials start with a funny skit that leads to the line, “just ok is not ok.” The commercials’ narrator then says something along the lines of: “AT&T is America’s best wireless network according to America’s biggest test.”

Here’s an example:

Alternate versions of the commercial involve ok babysitters, ok sushi, ok surgeons, and more.

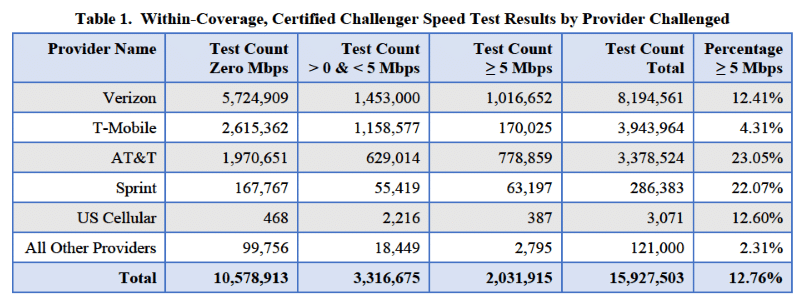

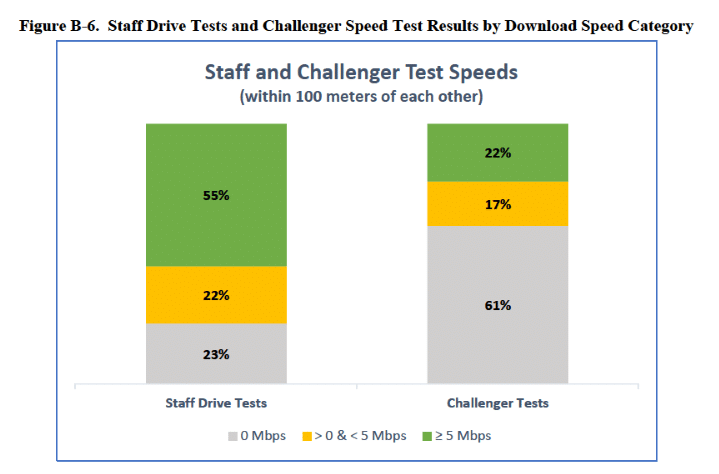

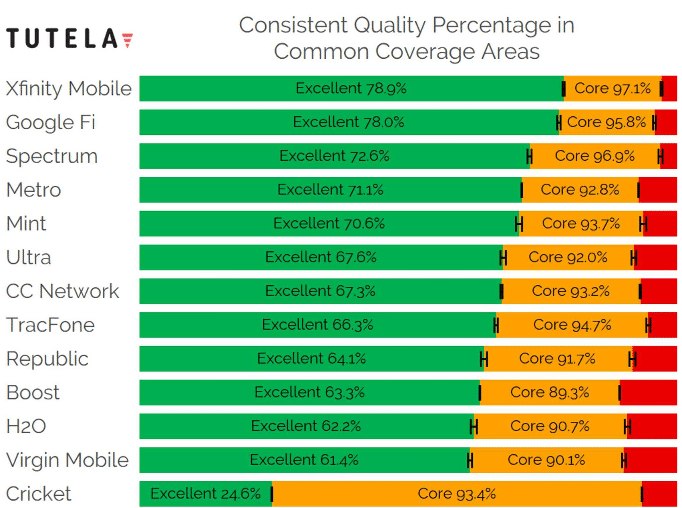

AT&T bases its “best network” claim on the results of Global Wireless Solutions’s (GWS) 2018 tests. The claim is at odds with the results of many other companies’ evaluations and my own view.

The meaning of the word “best” is ambiguous, but I’d guess that a survey of professionals in the wireless industry would find that most people consider RootMetrics to be the best evaluation firm in the wireless industry. Verizon fared far better than AT&T in RootMetrics’s most recent evaluation.

It’s unclear to me what AT&T is claiming when it calls GWS’s test, “America’s biggest test.” Is it the biggest test in terms of miles driven, data points collected, area covered, or something else? GWS may have the biggest test according to one metric, but it’s not unambiguously the biggest test in the nation.