Today, AT&T published a press release announcing upgrades for the Unlimited Elite plan, the most premium plan AT&T offers normal consumers.

Three major changes are taking effect:

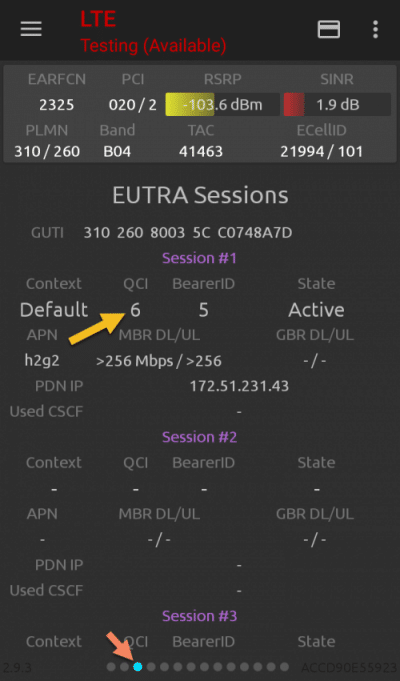

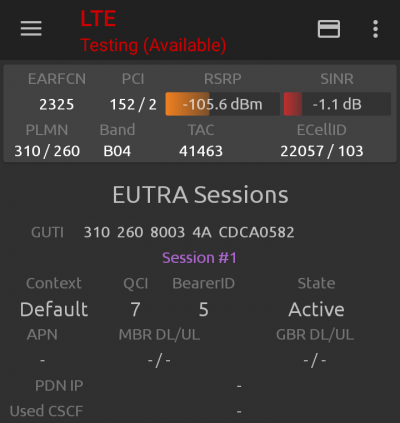

- Subscribers using over 100GB of data in a month will no longer be deprioritized.

- The mobile hotspot data allotment will increase from 30GB to 40GB.

- Video can now stream in resolutions up to 4k.

I’m unsure what’s going on with video resolution. As I noted in my Unlimited Elite Review, AT&T used to throttle video to about 480p by default. However, Unlimited Elite subscribers could opt out of throttling in their account settings. It could be that AT&T will no longer require subscribers on the Elite plan to opt out of video throttling. Alternatively, it might be that there used to be a secondary limit (1080p?) that affected customers who opted out of the standard, 480p throttle.

Don’t Buy The Hype

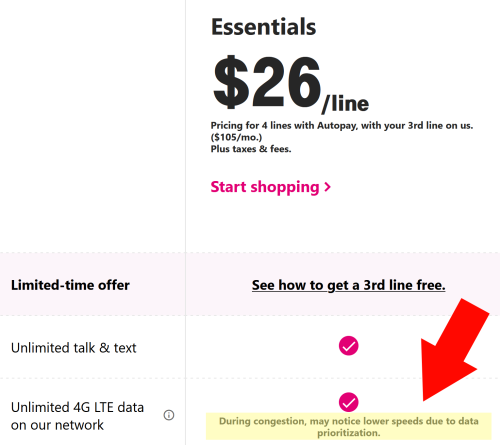

With these latest upgrades, it looks like AT&T is trying to match what T-Mobile did a few months ago when it dropped the deprioritization threshold on its most premium, consumer-grade plan. Here’s a bit I wrote at the time:

When T-Mobile made its announcement, industry journalists praised the company. I expect we’re going to see something similar following AT&T’s announcement. Don’t buy the hype. Network capacity is a limited resource. It doesn’t come from nowhere. If you give some subscribers more, other subscribers get less.