Google Fi uses an admirably simple pricing structure. A base rate of $20 per month offers subscribers unlimited talk and text. Beyond that, users are charged $10 per gigabyte of data. Single-line plans are capped at a monthly charge of $80, so subscribers that use 6GB of data will pay the same monthly price as subscribers that use 10GB of data.1 While I like the simplicity of the pricing structure, plans end up being fairly expensive. It’s my impression that Google Fi has had its current pricing structure in place for several years despite the cost per byte of data dropping in the industry at large.

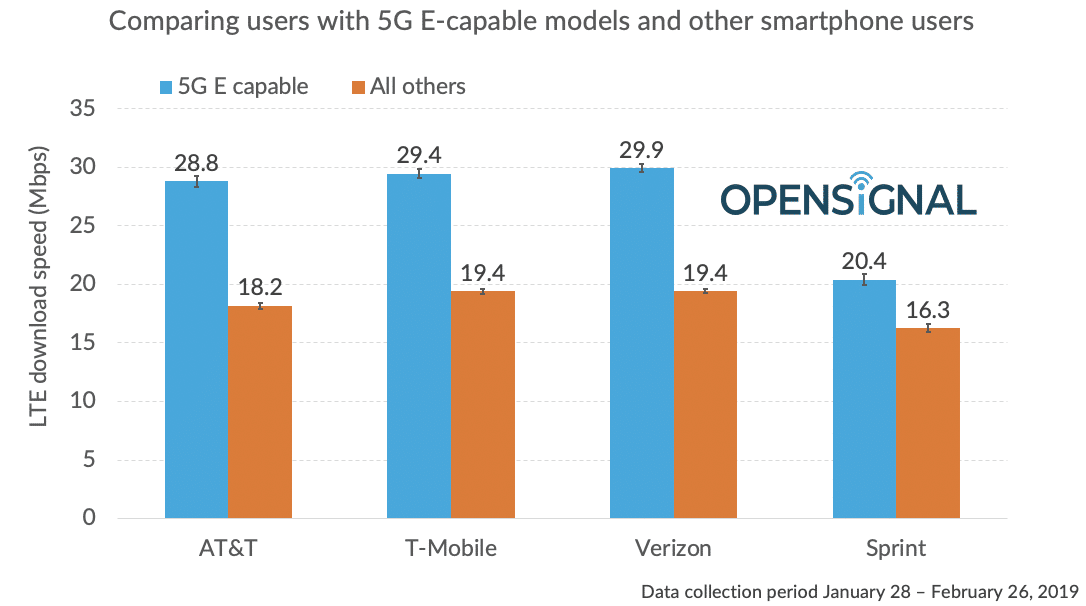

Fi-enabled devices have technology that allows them to switch between T-Mobile, U.S. Cellular, and Sprint’s networks. While the technology is cool, I’m not sure I’d choose seamless switching between three networks with mediocre coverage over exclusive access to Verizon’s more reliable network.2

Fi now officially supports devices that are not Fi-enabled. When these devices are used with Fi, they’ll only have access to T-Mobile’s network. Many mobile virtual network operators use T-Mobile’s network and offer far better prices than Fi. For example, Mint Mobile’s plans blow Fi’s prices out of the water.3 Even with a Fi-enabled device, I think most people can find a better deal. A light user would pay $30 per month before taxes and fees for texts, talk, and 1GB of data on Fi’s network. You could get the same unlimited texting, unlimited talk, and 1GB of data with Verizon’s prepaid service for $30.4 RedPocket can offer those resources on any of the major networks for $19 per month.5

For heavy data users, the case against Fi is even clearer. Using 6+ gigabytes of data brings the Fi monthly bill to $80 before taxes and fees. At that cost, I expect you could purchase an unlimited, postpaid plan with any of the Big Four carriers.

Despite my negativity, I’m still a huge fan of Fi’s simplicity and remarkable international roaming policies. Hopeful Fi will revamp its prices in the near future to become more competitive with the other options on the market.