The mobile virtual network operator BOOM! Mobile recently launched wireless plans that run over T-Mobile’s network. With this addition, BOOM! now offers three types of plans:

- Boom! Red – service over Verizon’s network

- Boom! Blue – service over AT&T’s network

- Boom! Pink – service over T-Mobile’s network

Many of the Boom! Pink plans have the same allotments of minutes, texts, and data as well as the same price points as previously existing Boom! Red plans. Boom! Blue plans with allotments equivalent to those in Pink and Red plans are sometimes available, but they tend to have higher price points.

BOOM! Mobile is also offering several Boom! Pink plans that are unlike the company’s previous offerings. These plans each offer a certain number of Flex Points. Each point can be redeemed for either 1 minute of calling, 1 text message, or 1MB of data.

- 450 Flex Points (7 Day Plan) – $5

- 900 Flex Points (14 Day Plan) – $10

- 3,000 Flex Points (Yearly Plan) – $60

My thoughts

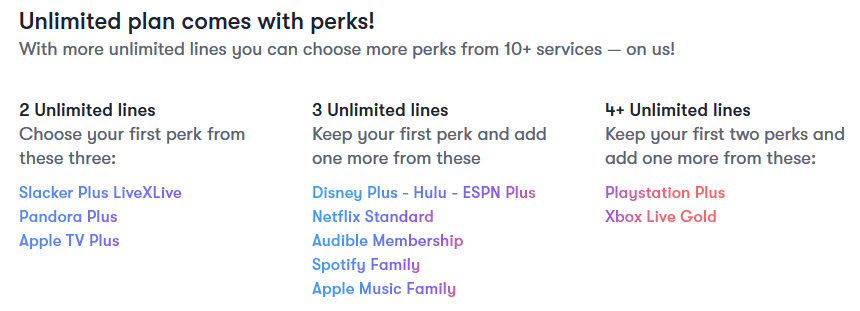

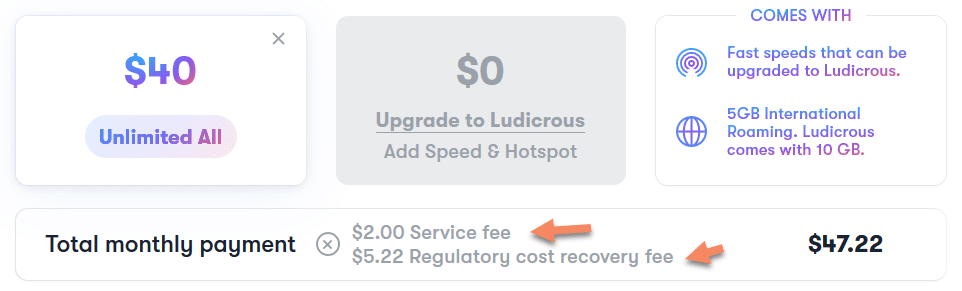

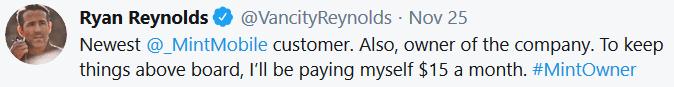

It’s great to see BOOM! Mobile expanding its offerings. For most consumers, I think the Red plans will continue to be the best option since (a) they aren’t more expensive than the Pink plans and (b) they run over Verizon’s extensive network. I expect most consumers looking for coverage over T-Mobile’s could find better deals with an alternative MVNO (e.g., Mint Mobile). Still, I’m glad to see BOOM! Mobile offering access to more networks. The new flex plans are particularly interesting. I’d love to see more carriers come out with plans that use similar structures.