In August, Helium Mobile launched a $5 per month unlimited plan that was exclusively available in the Miami area. At the time, I wrote:

Peter Adderton, founder of Boost Mobile and current CEO of MobileX, offered a valid correction:

@Coverage_Critic I corrected the story " it’s arguably the cheapest unlimited plan in miami ." 😀 https://t.co/RWGcTgMzIS

— Peter Adderton (@peter_adderton) August 17, 2023

Nationwide Service – $20 Per Month

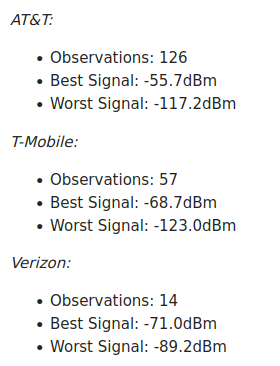

Today, Helium Mobile launched expanded service. While $5 per month pricing continues for those in the Miami area, people throughout the US can now get service for $20 per month plus taxes.

It’s a pretty sweet deal for what’s essentially T-Mobile service. I’m not confident it’s the cheapest unlimited plan in the US, but it’s a strong contender. In all but the most tax-intensive locations, I think Helium Mobile comes out cheaper than unlimited plans from US Mobile and Visible that start at $25 with taxes baked in.1

2 Points People Miss

I’ve been disappointed by the press coverage of Helium Mobile (both positive and negative). Journalists are missing two key points:

- The Helium project has an ambitious goal of building out a network that could allow Helium Mobile to achieve cost savings over conventional MVNOs. Meaningful cost savings have not been achieved yet.

- Today, Helium Mobile’s low prices are enabled by what’s effectively a subsidy from investors.

While a $20 plan may not be as unprofitable as a $5 plan, a small MVNO will still take significant losses on a mass-market plan at that price point. That said, it’s pretty normal for new carriers to offer plans that aren’t profitable in hopes of one day reaching economies of scale or achieving new kinds of cost-efficiency.

How Much Does The Average American Pay For Cell Service?

In a Tweet, Helium Mobile compared its $20 per month rate to a $157 per month figure from JD Power. The latter figure allegedly represents what the average American spends on their phone plan.

IT'S HERE🔥

Our nationwide $20/month Unlimited Phone Plan is now available!The average American spends $157/month on their phone plan, but starting today, anyone in the US can join Helium Mobile & say goodbye to overpriced bills.🙌

Read the news: https://t.co/qXWCpm6zbo

Sign… pic.twitter.com/A2hqPppCMB— Helium Mobile (@helium_mobile) December 5, 2023

In a press release, Helium Mobile doubles down on the comparison and describes its new offering as such:

$157 is the wrong number for the comparison Helium Mobile is making. It’s way too high.

JD Power charges for access to the study, so I’ll only speculate. I’d guess JD Power is looking at the average expenditure of entire households. Most households have multiple people and multiple phone lines. Perhaps the costs of device subsidies or device financing are also sneaking into JD Power’s numbers.

I don’t think prospective customers are being harmed. People care about (1) what they pay for their current carrier and (2) how much less they might pay for Helium Mobile. The average American is irrelevant. Perhaps the comparison could confuse investors, but I doubt many are getting fooled. More than anything else, pushing the $157 statistic makes Helium Mobile look silly.