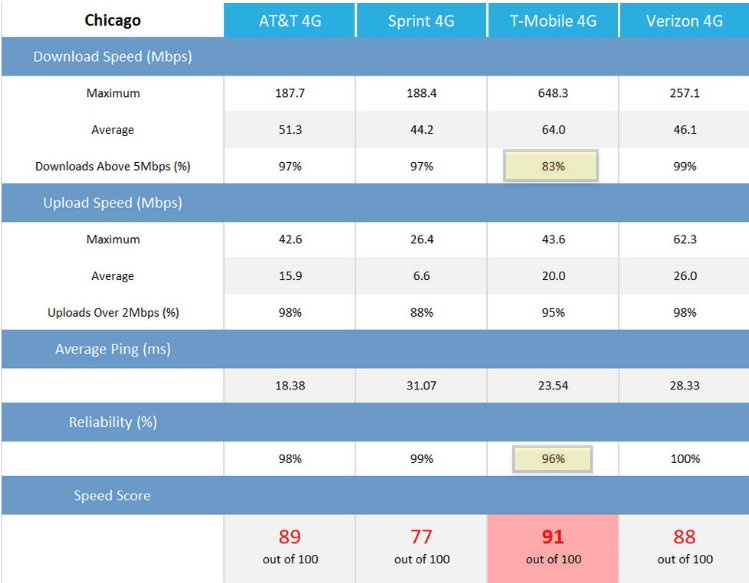

Yesterday, RootMetrics released its report on mobile network performance in the first half of 2019. Here are the overall, national scores for each network:1

- Verizon – 94.8 points

- AT&T – 93.2 points

- T-Mobile – 86.9 points

- Sprint – 86.7 points

While Verizon was the overall winner, AT&T wasn’t too far behind. T-Mobile came in a distant third with Sprint just behind it.

RootMetrics also reports which carriers scored the best on each of its metrics within individual metro areas. Here’s how many metro area awards each carrier won along with the change in the number of rewards received since the last report:2

- Verizon – 672 awards (+5)

- AT&T – 380 (+31)

- T-Mobile – 237 (-86)

- Sprint – 89 (+9)

My thoughts

Overall this report wasn’t too surprising since the overall results were so similar to those from the previous report. The decline in the number of metro area awards T-Mobile won is large, but I’m not sure I should take the change too seriously. There may have been a big change in T-Mobile’s quality relative to other networks, but I think it’s also possible the change can be explained by noise or a change in methodology. In its report, RootMetrics notes the following:3

I continue to believe RootMetrics’ data collection methodology is far better than Opensignal’s methodology for assessing networks at the national level. I take this latest set of results more seriously than I take the Opensignal results I discussed yesterday. That said, I continue to be worried about a lack of transparency in how RootMetrics aggregates its underlying data to arrive at final results. Doing that aggregation well is hard.

A final note for RootMetrics:

PLEASE DISCLOSE FINANCIAL RELATIONSHIPS WITH COMPANIES YOU EVALUATE!